Personality in Financial Decisions and Financial Crises

The American Psychological Association defines personality as “individual differences in characteristic patterns of thinking, feeling and behaving”.1 The concept of personality is usually associated with the field of psychology. However, this is not the only area in which the study of personality is applicable. Understanding personality and biases can help us examine how and why people make decisions. This doesn’t simply mean everyday decisions like what to watch on TV – it extends to the world of business, where personality can play a hidden role in how financial decisions are made.

Understanding bias

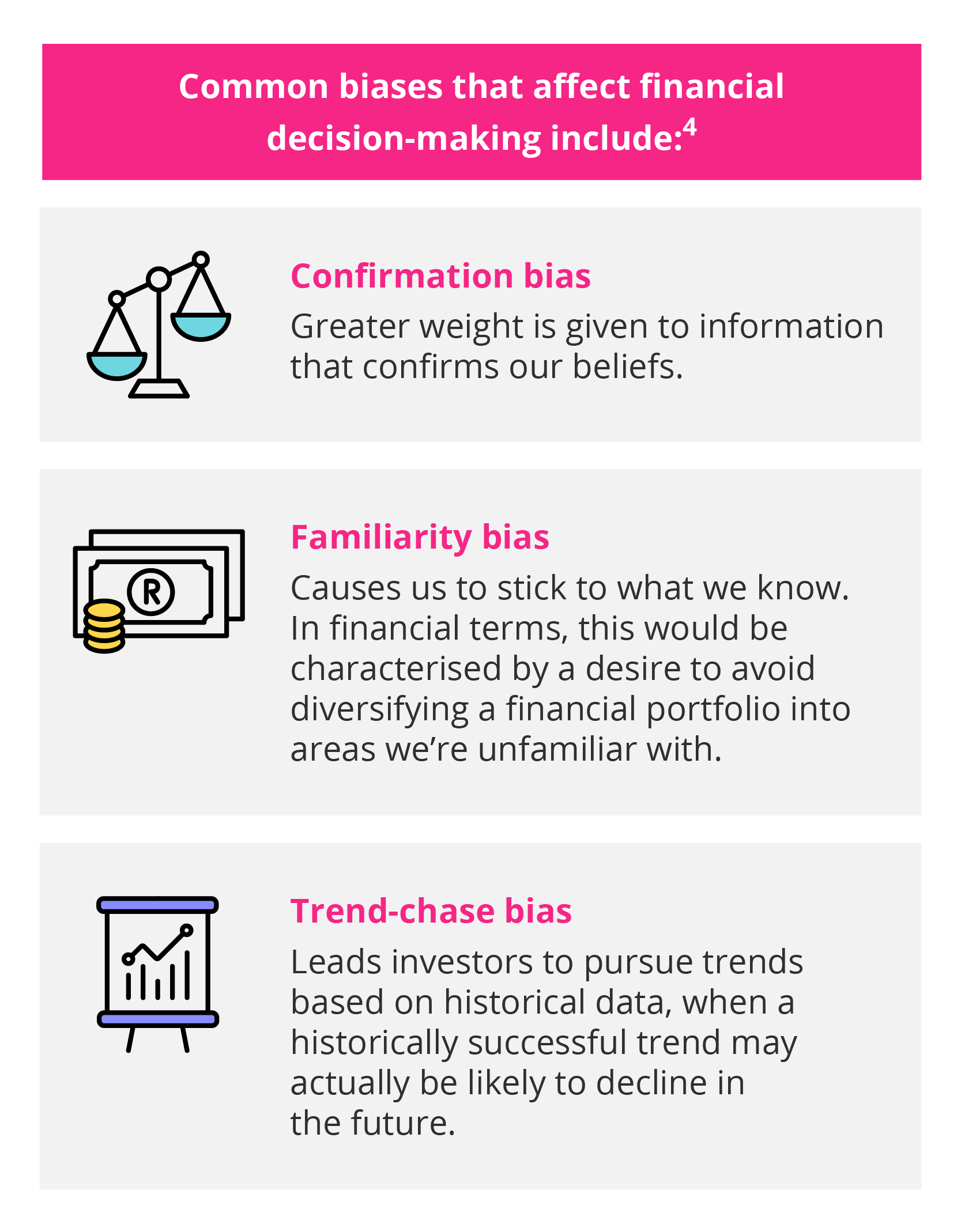

There are a host of potential biases that can influence decision-making…

One of the key ways that our decision-making is affected is through bias. Bias is defined by the Cambridge English Dictionary as “the action of supporting or opposing a particular person or thing in an unfair way, because of allowing personal opinions to influence your judgment”.2

The origins of bias, despite the dictionary definition, are not necessarily negative. Biases are our brain’s way of simplifying complex problems, essentially allowing us to make decisions more quickly, and avoid decision paralysis when confronted by large problems. This has made them an effective survival tactic throughout history.3 Unfortunately, these biases can quickly become problematic in a financial setting, as they can cause us to overlook pertinent data.

This list is far from exhaustive, but it does show that financial decision-making is often more affected by our own personal beliefs than we may realise.

Personality and financial decision-making

In their discussion of the 2008 financial crisis, the authors of the paper ‘Psychology, financial decision making, and financial crisis’ highlight the apparently irrational behaviour of market actors – both investors and institutions in operation at the time – whose actions ultimately brought the financial market to its knees.5 However, these actions may not be quite as irrational as they appear. Instead, they can be seen as the result of specific and regular behaviours. In other words, functions of the actors’ personalities.6

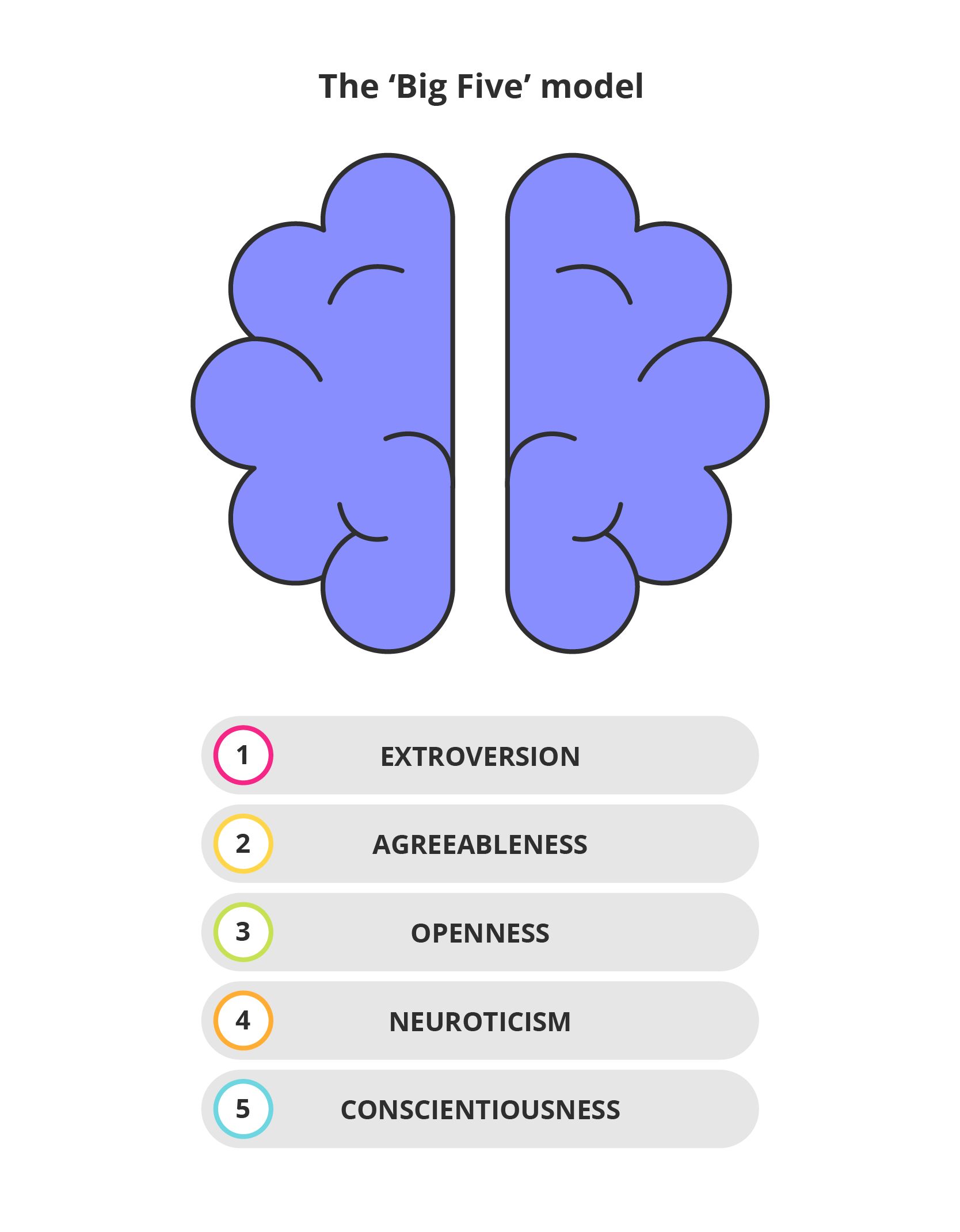

There are various ways to describe underlying personality traits. One method is often referred to as the ‘Big Five’ model, which describes the five essential building blocks that make up our personality:7

Of the ‘Big Five’, the trait most closely associated with financial decision-making is conscientiousness. This trait governs thoughtfulness, impulse control, and goal-directed behaviours, and was directly linked to the ability to preserve wealth during the 2008 financial crisis.8

Conscientiousness as a personality trait in financial decision-making is tied to impulsivity: the less conscientious you are, the more likely you are to undertake impulsive, or risky behaviour.9 Those who rank highly in conscientiousness, by contrast, are more likely to plan carefully before making a decision, and are therefore less risk-prone.

These behavioural traits were on full display during the lead-up to the 2008 financial crisis, in both consumers and bankers. Subprime mortgage lending grew quickly, attractive to consumers who saw the chance to own their homes, and to bankers for their high return. Bankers even found a way to profit twice by repackaging the loans to other investors.10 The financial downfall came swiftly: raised interest rates, combined with a lower housing market, meant that many borrowers were unable to continue paying back their loans, and the knock-on effect on banking institutions eventually led to a full global recession.11

While this is a simplification of the many complex factors that fed the 2008 financial crisis, it’s illustrative of the role that risk-taking behaviour can play when allowed to run unchecked. It also shows the power our personalities have in the decisions we make: a single aspect of our personality can have a disproportionate effect on the decisions we make, even in supposedly logical pursuits.

This begs the question: how can you improve your financial decision-making if it’s partly out of your hands? The answer is that you can learn to change.

Personal growth for better decision-making

Conscientiousness as a personality trait in financial decision-making is tied to impulsivity…

It’s easy to fall into the trap of thinking that your personality is ultimately immutable, but the truth is that, if you truly want to, you can change and improve each of the Big Five personality traits. There are several ways to go about improving your conscientiousness. According to research presented in the Harvard Business Review, you can increase your engagement in activities based on specific criteria, by performing actions that:12

- Feel important

- Are enjoyable

- Align with your values

The authors of the above research argue that making this change is as much about the way you think about the work you’re doing, as it is about the work itself. If, for example, your decision-making is poor because you consider the decisions inconsequential, considering the broader impact of your choices can help make them feel more significant – ultimately allowing you to take a more considered approach.

Alternatively, you can take advantage of another option to improve decision-making, one that can significantly offset personality as a factor: technology.

Technology and financial decision-making

Ensuring that the right technology is in place is a vital first step to gaining insight through data.

The increasing access to data, and the technologies that allow us to manipulate and analyse it, stands to have a large impact on the way decisions are made in business. Consider algorithmic trading: This computational trading method has been around since the 1970s at least.13 It uses complex algorithms to automate specific trade strategies, allowing them to be carried out much faster than a human could. The process largely removes the possibility of human error, since the trades are placed by a machine. Algorithmic trading also mitigates the potential for bias, as trading is based strictly on the strategy being used, and is not swayed by the same emotional considerations that humans are.14

The advent and rise of the internet has made a vast wealth of information available for decision makers. However, it can be daunting trying to disseminate the useful information. Data technology provides that assistance; the means to collect and make use of data for the purpose of improving decision-making is driven by computers and analytics programmes.15

Ensuring that the right systems are in place is the first step to gaining insight through data.16 There is a wide array of analytics platforms available to businesses that provide access to tailored and useful information that can be utilised for effective decision-making.17 In order to get to these insights, however, you’ll need an effective data analytics team.

This can be costly to implement: spending on big data is expected to reach a staggering $103 billion by 2027.18 But the long-term benefits outweigh the initial investment. When used properly, data can be utilised to make better decisions and benefit companies, both through cost reduction – by increasing productivity and reducing inefficiencies – and revenue growth, by improving aspects such as sales performance or reducing customer attrition.19

In order to effectively utilise the technological advantage of analytical tools, it’s important to recognise the biases and personal traits that influence our thinking without us even realising it.

Research shows that technology also offers positive outcomes for decision-making: in one particularly illuminating study, researchers used an algorithm to select board members for a given company. They found that the companies performed better with their candidates. Other examples highlight the potential for algorithms to create more equitable businesses, for instance, ensuring that mortgages are available to underserved communities, while maintaining profitability.20

However, data analytics is not the silver bullet for astute financial decision-making. Analytics can only ever mitigate the effect of personality on decision-making. Inherent biases in decision-making can be reduced, but not eliminated as long as the human element remains. After all, it’s a simple matter to disregard insights in favour of ‘following your gut’.

In order to effectively utilise the technological advantage of analytical tools, it’s important to recognise the biases and personal traits that influence our thinking. Introspection may seem like a strange way to make decisions in business, but ultimately, it provides us with a basis from which to approach decisions with a clear eye. With the addition of technologies that are specifically designed to reduce the role of bias, we can dramatically improve our chances of success in the world of business.

- 1 (Nd). ‘Personality’. Retrieved from the American Psychological Association. Accessed 12 April 2019

- 2 (Nd). ‘Bias’. Retrieved from the Cambridge English Dictionary. Accessed 12 April 2019

- 3 Cherry, K. (Nov, 2018). ‘How cognitive biases influence how you think and act’. Retrieved from Very Well Mind.

- 4 Sherman, B. (Sep, 2017). ‘8 common biases that impact investment decisions’. Retrieved from Investopedia.

- 5 Gärling, T., Et al. (2009). ‘Psychology, financial decision making, and financial crisis’. Retrieved from Semantic Scholar.

- 6 Gärling, T., Et al. (2009). ‘Psychology, financial decision making, and financial crisis’. Retrieved from Semantic Scholar.

- 7 Cherry, K. (Mar 2019). ‘The big five personality traits’. Retrieved from Very Well Mind.

- 8 Duckworth, A.L., & Weir, D. (Dec 2011). ‘Personality and response to the financial crisis’. Retrieved from Core.

- 9 Cherry, K. (Mar 2019). ‘The big five personality traits’. Retrieved from Very Well Mind.

- 10 Singh, M. (Mar, 2019). ‘The 2007-08 financial crisis in review’. Retrieved from Investopedia.

- 11 Singh, M. (Mar, 2019). ‘The 2007-08 financial crisis in review’. Retrieved from Investopedia.

- 12 Tasselli, S., et al. (Mar, 2018). Becoming more conscientious’. Retrieved from Harvard Business Review.

- 13 Chen, J. (Feb, 2019). ‘Algorithmic trading’. Retrieved from Investopedia.

- 14 Chen, J. (Feb, 2019). ‘Algorithmic trading’. Retrieved from Investopedia.

- 15 Bekker, A. (Mar, 2018). ‘The “Scary” Seven: big data challenges and ways to solve them’. Retrieved from Science Soft.

- 16 Linton, I. (Sep, 2017). ‘How does technology affect business decisions?’. Retrieved from BizFluent.

- 17 Singh, H. (Dec, 2018). ‘Using analytics for better decision-making’. Retrieved from Towards Data Science.

- 18 Albertson, M. (Mar, 2018). ‘Software, not hardware, will catapult big data into a $103B business by 2027’. Retrieved from Silicon Angle.

- 19 Ghandi, S., Et al. (Nov, 2018). ‘Demystifying data monetization’. Retrieved from MIT Sloan Management Review.

- 20 Miller, A.P. (Jul, 2018). ‘Want less-biased decisions? Use algorithms’. Retrieved from Harvard Business Review.