Healthcare Financing and the Sustainability of Health Systems

The average person’s income is unable to keep up with the rising cost of healthcare. “Good health is the foundation of a country’s human capital, and no country can afford low-quality or unsafe healthcare,” says World Bank Group President Jim Yong Kim.1 Access to reliable, affordable health services ensures healthier people who aren’t being pushed into poverty. Universal health coverage, therefore, plays an important role in sustainable development and poverty reduction.

A report by the Federal Reserve Board found that 44% of adult Americans could not come up with the $400 required in a medical emergency without turning to credit cards, family and friends, or selling off possessions, and 25% skipped medical treatments altogether due to unaffordability.2 Sustainability through universal health coverage can ensure health services are made available to those who need them most, at the time they need it most. Reducing a country’s dependency on direct, out-of-pocket payments for healthcare removes any financial barriers to access, and lowers the financial impact of health payments.3

What is universal health coverage, or National Health Insurance (NHI)?

The main premise of healthcare financing is a pooling of funds in order to ensure healthcare needs are met, irrespective of an individual’s socioeconomic status.4 Universal health coverage provides access to vital health services, such as prevention, promotion, treatment, rehabilitation and palliative care, without the often restrictive, financial burden of having the funds on hand to pay for these services.5

For this to be effectively implemented, an efficient health system is needed to provide an entire population with quality services, health workers, medicines and technologies, as well as a finance system that will protect people that can’t afford to pay expensive medical fees.6 With this in mind, it is clear that universal health coverage cannot be achieved overnight, but countries can take steps to move towards it, or to maintain the gains they’ve already made.7

The financial sustainability of health systems

Phasing in universal healthcare to a country is an enormous undertaking financially. It is estimated that $274-371 billion will need to be spent on healthcare systems per year until 2030, in order for universal healthcare coverage (UHS) to be implemented. This accounts for only 67 countries, which represent 95% of the total population in low-income and middle-income countries.8

Around 75% of that spend will go towards health systems, with health workforce, infrastructure and medical equipment being the main cost drivers. Should this be successfully implemented, with gap funding from the World Health Organisation (WHO), up to 97 million lives could be saved, and life expectancy could increase by 3.1 to 8.4 years, depending on the country profile.

Image: Conceptual framework for transforming health systems towards SDG Three targets. Overall contextual factors include climate change, poverty, migration, and changes in the level and distribution of wealth. Country-specific contextual factors include epidemiological and demographic transitions, urbanisation, and recovery from conflict and disasters.

Universal healthcare financing that works

In 1948, WHO declared healthcare a basic human right, and as a result the demand for universal healthcare was born.9 Since then, many countries have successfully implemented sustainable health systems, thus ensuring doctors and hospitals provide citizens with quality care at an affordable rate, and using their financial leverage to influence healthcare providers.10

Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Singapore, and Switzerland use the healthcare financing model where the government pays private companies to deliver healthcare services to its citizens.11 In the United Kingdom, the government both provides and finances the healthcare system.12

Implementing a national health financial system

The United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals address global challenges faced by everyone, including poverty, inequality, climate, environmental degradation, prosperity, and peace and justice.13 One of these goals is to achieve universal health coverage, making provision for financial risk protection, giving access to quality essential healthcare services and access to safe, effective, and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all.

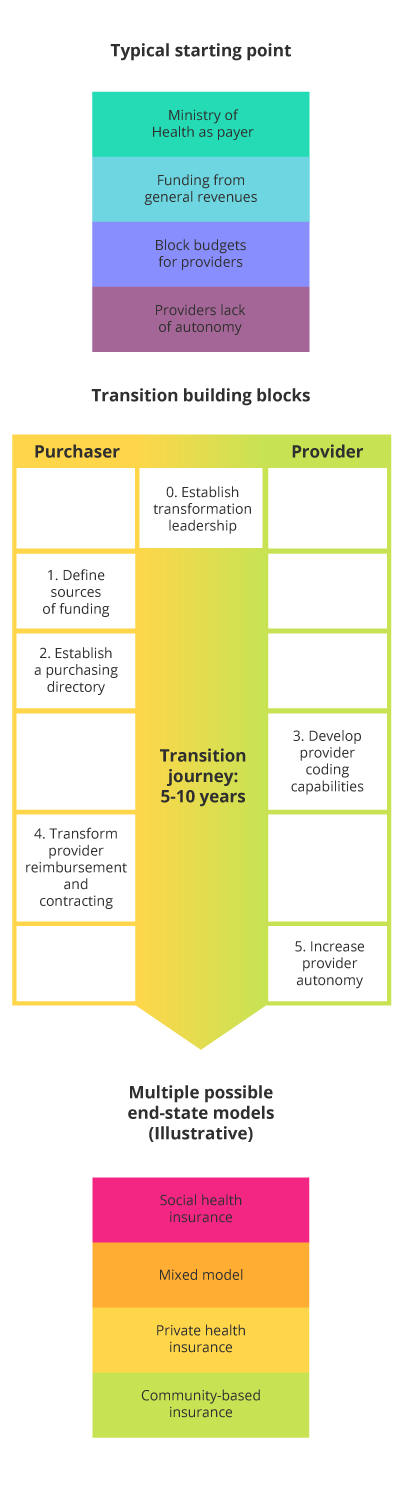

According to McKinsey, a set of building blocks are needed before health system financing can transform emerging economies. These blocks create a cohesive system that will assist in delivering the best value for a country’s population.14

- Start at the top. A strong commitment from the country’s leadership will ensure a successful health system transformation.

- Additional funding. Regardless of the objective of healthcare financing, additional sources of funding will be required.

- Who is purchasing? The ‘payer’ and ‘provider’ functions should be separated early on. Identifying a strategic purchaser organisation makes it easier to clarify responsibilities across typically rigid healthcare systems. It also opens the door for the introduction of market forces and performance-based competition across providers.15

- Develop coding for payments. Providers will need to invest in coding capabilities in order to develop payment systems, and purchasers will need to develop auditing capabilities in order to control data quality.

- Reimburse providers. A well-developed reimbursement model will incentivise providers to provide quality healthcare services in an efficient, cost-effective manner.

- Increase provider autonomy. Autonomy can be granted to providers in three broad areas: financial management, personnel management, and the delivery of social services.

A sustainable approach would be to start slowly by increasing the number of health services, while simultaneously lowering the out-of-pocket costs to patients over time.

Challenges of implementing national health financial systems in developing economies

The biggest challenge for many emerging economies is that essential health services for diseases such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), tuberculosis, malaria, non-communicable diseases and mental health, sexual and reproductive health and child health, should be available to all who need them. However, given the proliferation of these diseases and the young population in low-income countries, these services cannot be offered to everyone at an affordable price.16

This is illustrated in Ethiopia’s Healthcare Financing Strategy (2015–2035). While the government is working toward universal health coverage, it acknowledges the challenges it faces to do so:17

- It has one of the lowest per-capita health expenditures in the world ($21)

- It leans heavily on donor funds (50% of total health spending)

- It’s out-of-pocket payments for medical services accounts for 34% of total health spending

It’s not uncommon for countries to combine universal health coverage with other financing models in order to foster healthy competition. Models such as: pay-as-you-go, prepay, and private healthcare insurance could serve as a means to potentially lower costs in a bid to be competitive, provide people with more healthcare alternatives, and potentially improve patient care.18

- Pay as you go. This is as simple as arriving at a doctor, and paying for the cost of his time, and the medication. The financial benefit is that there are no monthly premiums, however, the financial risk is that the visit to the doctor or hospital could be crippling without insurance.

- Prepaid health insurance.19 This is where a monthly amount is paid to a health insurance provider in order to mitigate the unforeseen expenses of a hospital or doctor visit. The benefit of this is that the payments are more affordable than the hefty once-off, pay-as-you-go approach. However, there are often limitations set by the insurance provider, depending on the scheme.

- Private healthcare insurance.20 This is where health insurance schemes are financed through private insurance premiums, or payments that a policyholder makes to cover medical expenses. This could be an employer who self-insures health coverage instead of contracting it to an insurance company.

Additional investments required in 67 low-income and middle-income countries to meet Sustainable Development Goal Three (US$2014 billion) (A) and additional resource needs by service delivery platform (B) in the ambitious scenario. Additional health programme costs include those that are programme-specific, but do not refer to specific drugs, supplies, or laboratory tests. Examples include costs for programme-specific administration staff, supervision, and monitoring relative to the services for which the programme provides leadership and oversight (e.g. the national malaria programme provides implementation guidance, and monitors and supervises service delivery for malaria). Other examples include mass media campaigns and demand generation.

Both businesses and investors are essential to support a country’s efforts of financing healthcare and providing sustainable health systems as part of the United Nation’s 169 targets,21 along with the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).22 Fundamentally, the basic building blocks of implementing healthcare financing are universal to all health system transformations, regardless of what model is chosen for implementation. These building blocks can serve to create tangible economic benefits and assist with the collection of new data that will inform policy and legislation makers going forward.23

- 1 Hartl, G. (Jul, 2018). ‘Low quality healthcare is increasing the burden of illness and health costs globally’. Retrieved from WHO.

- 2 (May, 2017). ‘Federal Reserve Board issues report on the economic well-being of U.S. households’. Retrieved from FRB.

- 3 (Nd). ‘Questions and answers on universal health coverage’. Retrieved from WHO. Accessed 17 March 2019

- 4 (Nd). ‘National Health Insurance’. Retrieved from South African Government.

- 5 (Nd). ‘Questions and answers on universal health coverage’. Retrieved from WHO.

- 6 (Nd). ‘Questions and answers on universal health coverage’. Retrieved from WHO.

- 7 (Nd). ‘Questions and answers on universal health coverage’. Retrieved from WHO.

- 8 Stenberg, K., et al. (Sep, 2017). ‘Financing transformative health systems towards achievement of the health Sustainable Development Goals: a model for projected resource needs in 67 low-income and middle-income countries’. Retrieved from Lancet.

- 9 (Nd). ‘What is health financing for universal coverage?’. Retrieved from WHO.

- 10 Amadeo, K. (Mar, 2019). ‘Universal health care in different countries, pros and cons of each’. Retrieved from the Balance.

- 11 Carroll, A., et al. (Sep, 2017). ‘The best health care system in the world: which one would you pick?’. Retrieved from the New York Times.

- 12 Post, L. (Nov, 2018). ‘Big data helps UK National Health Service lower costs, improve treatments’. Retrieved from Forbes.

- 13 (Nd). ‘About the Sustainable Development Goals’. Retrieved from UN. Accessed 29 April 2019

- 14 Hediger, V. (Apr, 2018). ‘Health system financing: tips for emerging markets’. Retrieved from McKinsey.

- 15 Jakab, M., et al. (2002 – 2006). ‘The introduction of market forces in the public hospital sector’. Retrieved from World Bank.

- 16 (Nd). ‘Questions and answers on universal health coverage’. Retrieved from WHO. 17 March 2019

- 17 Hediger, V. (Apr, 2018). ‘Health system financing: tips for emerging markets’. Retrieved from McKinsey.

- 18 Amadeo, K. (Mar, 2019). ‘Universal health care in different countries, pros and cons of each’. Retrieved from the Balance.

- 19 Fleck, F., et al. (Sep, 2012). ‘Expanding prepayment is key to universal health coverage’. Retrieved from WHO.

- 20 (Nd). ‘Private healthcare insurance’. Retrieved from OECDStat. Accessed 23 April 2019

- 21 (Nd). ‘About the Sustainable Development Goals’. Retrieved from the UN.

- 22 (Nd). ‘Sustainable Development Goals’. Retrieved from Sustainable Development.

- 23 Hediger, V. (Apr, 2018). ‘Health system financing: tips for emerging markets’. Retrieved from McKinsey.