Top 5 Effective Negotiation Skills

Negotiating is not limited to boardrooms of big organisations, but is a skill that you use each day. Yet, despite negotiation being common practice, it carries a largely negative association and many people dread having to negotiate. This largely stems from the misconception that negotiators always want opposite outcomes. The idea that negotiators are in conflict with one another is not always correct, and is known as the assumption of false conflict.1 Negotiation shouldn’t be a battle or a constant compromise, and a basic understanding of some fundamental concepts can open up possibilities for mutual gain.

Back and forth communication designed to reach an agreement when you and the other side have some interests that are shared and others that are opposed

In Getting to Yes, writers Roger Fisher, William Ury, and Bruce Patton highlight how negotiation doesn’t need to be competitive battle. They define negotiation as “a back and forth communication designed to reach an agreement when you and the other side have some interests that are shared and others that are opposed”.2 This definition encompasses how negotiations can be multifaceted and can have many possible outcomes. Five principles of effective, ‘win-win’ negotiations are explained below.

1. Preparation

Negotiating success is ensured by preparation. According to employee training specialist, Procurement Academy,

Negotiation is a process, not an event, and much of what goes into a successful negotiation is planning. In her book The Mind and Heart of the Negotiator, Northwestern University Professor Leigh Thompson highlights two questions to ask yourself as you prepare for an upcoming negotiation:4

- What do I want?

- What is my best alternative to reaching an agreement?

What do I want?

What you want in a negotiation is called your target point (TP).5 To determine your TP, you must understand your interests. Your interests are the ‘why’ of the negotiation – the reason behind your position.6 The better you understand your ‘why’, the better you can define your TP, and develop creative ways to achieve it.

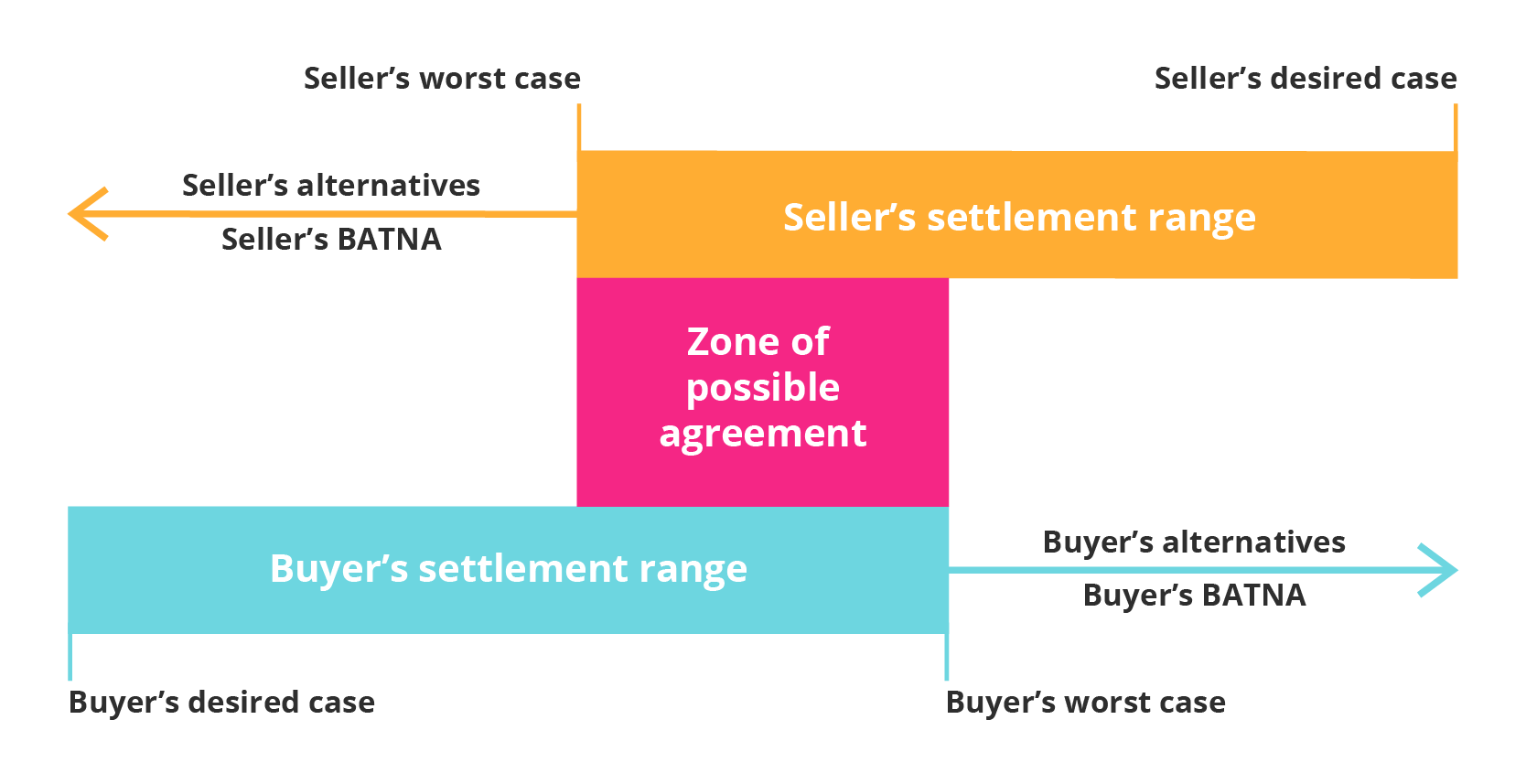

However, as your TP is your ideal outcome, unless you have made an error of judgement, it is unlikely to be accepted.7 This is why it’s equally important to determine what you don’t want. What you don’t want, or the absolute lowest offer or outcome you would accept, is your reservation point (RP).8 Rather than being arbitrary, your RP involves assessing all of your options and alternatives to reaching an agreement. Assessing an offer in relation to your alternatives encourages you to think critically about whether the offer is good, or whether you are better off opting for an alternative instead of reaching an agreement. The difference between your target point and reservation point is your bargaining range, or the range within which you’ll aim to negotiate. If you receive an offer that is below your RP, and not within your bargaining range, you should resort to your best alternative.

What is my best alternative to reaching an agreement?

The alternative to your highest expected value should be selected as your best alternative to a negotiated agreement (BATNA).9 If the negotiation isn’t going as you planned and an agreement doesn’t seem likely, your BATNA is your safeguard for a favourable outcome.10 It’s the measure by which you should judge any proposed agreement, and the only standard that can protect you from accepting an offer that is too low, or mistakenly rejecting an offer that is actually beneficial to you.11 Unlike your target point and reservation point, your BATNA is external to the negotiation. It’s not affected by anything the other party does or says, and a strong BATNA is your greatest asset in a negotiation. 12

For example, your goal might be to sell your car for X amount in order to put a down payment on an apartment. There is high demand, and you are approached by a buyer soon after advertising. While the buyer is not willing to pay your asking price, they are willing to negotiate. Two days later you are approached by a second buyer. If you are not able to reach a favourable agreement with the first buyer, reaching one with the second buyer would be your BATNA. In this scenario, this would be considered a strong BATNA because even if you don’t reach an agreement with the first buyer, you still have the opportunity to reach your goal of putting a down payment on an apartment. However, in a situation where there is low demand, only the first buyer may approach you. Your BATNA may be to keep the car or rent it out, neither of which are appealing to you, as they don’t help with the payment. This would be considered a weak BATNA, because if you aren’t able to reach an agreement with the first buyer, you may not reach your goal.

While your target point and interests will be discussed in the negotiation, it’s important not to reveal your reservation point. Whether you reveal your BATNA will depend on the circumstances, but if you have a weak BATNA, it’s usually not wise to reveal it to the other party, as it could give them more bargaining power in the negotiation.13

2. Know your counterparty

During your planning, your goal is to have a clear idea of what is important to you going into the negotiation. However, it can be easy to overlook that it’s equally important to consider what the other party wants. Through prior research, you need to gain insight into who your counterparty is, and try to understand their side of the negotiation. Debate their interests, issues, and their position.14 Ideally, you should consider what their TP, RP, and BATNA might be in the same level of detail which you consider your own.

Understanding this will help you determine where your bargaining zone lies. Your bargaining zone is the difference between your reservation point and theirs, or where your bargaining ranges overlap.15 This can be called the zone of possible agreement, meaning any agreement reached within this zone would be agreeable to both parties.

3. Integrative negotiation

Negotiation doesn’t have to be a win-lose situation where one party gets more and the other less. The premise of integrative negotiation involves each party trying to come to an agreement beneficial to both sides, creating a win-win situation.16

If you imagine the issue you’re negotiating to be a pie, if you get a bigger piece of the pie, the other party will have to get a smaller piece. This is known as the fixed-pie fallacy, and integrative negotiation aims to overcome this by growing the pie to increase its value. There are different techniques to do this, but understanding the other party’s interests and building trust are the building blocks of all integrative methods. Asking questions and listening are integral to integrative negotiation, as well as sharing your own interests. Behaviours in a negotiation are often reciprocated, so giving away some information could encourage the other party to do the same. When sharing information, it’s wise to share information that will inspire wise trade-offs.17

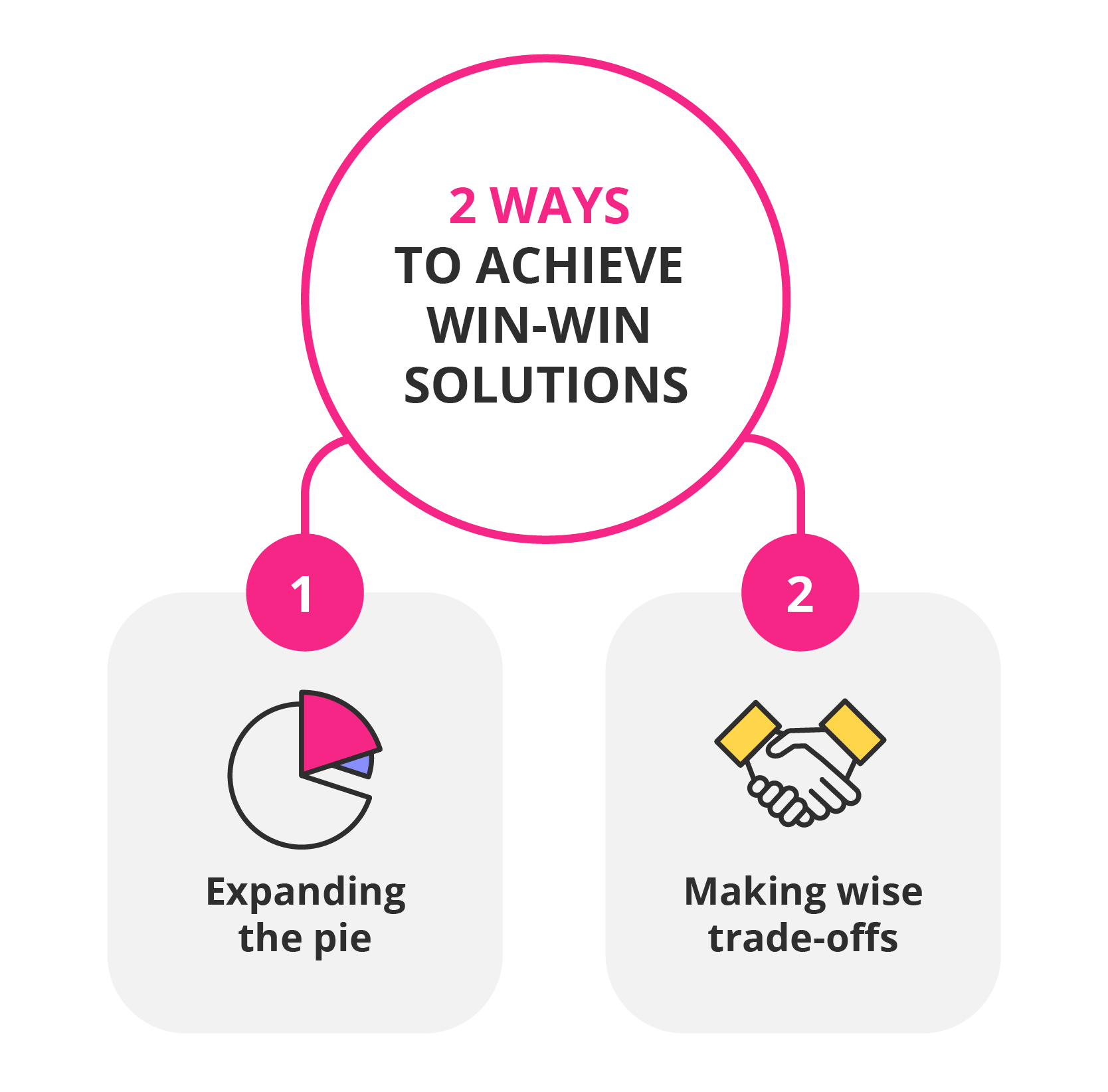

Expanding the pie

The simplest way to understand how to expand the pie is to think of it in terms of a salary discussion. Initially, it might appear as though there is a single issue on the table between the employee and the employer, being the value or amount of the salary. If this is the case, it would be true that the higher the salary the employee gets, the lower the employer’s budget becomes, and the negotiation is a simple win-lose scenario. However, if there were more issues on the table to negotiate, it’s possible to create a situation where everyone is happy. By factoring in holiday time, remote working opportunities, bonuses, medical aid coverage, retirement packages, and any other relevant issues, it’s more likely each party will walk away feeling as though they have gained something. If the employee values working from home because they have small children, the employer might be able to offer a slightly lower salary by incorporating a work-from-home option into the contract. This is one example of how both parties win by expanding the pie, or unbundling the issue.18 The more creative you are in unbundling, the more opportunities you can create for win-win situations.

Wise trade-offs

More often than not, negotiators value things differently. When you have multiple issues on the table, you can capitalise on this by giving each side more of what they really want. Try to identify issues that your counterpart values highly, but are less significant to you, and propose making a concession on those issues in exchange for something you value highly.19 This helps create agreements where if one party gets what they want, it doesn’t make the other party any worse off.

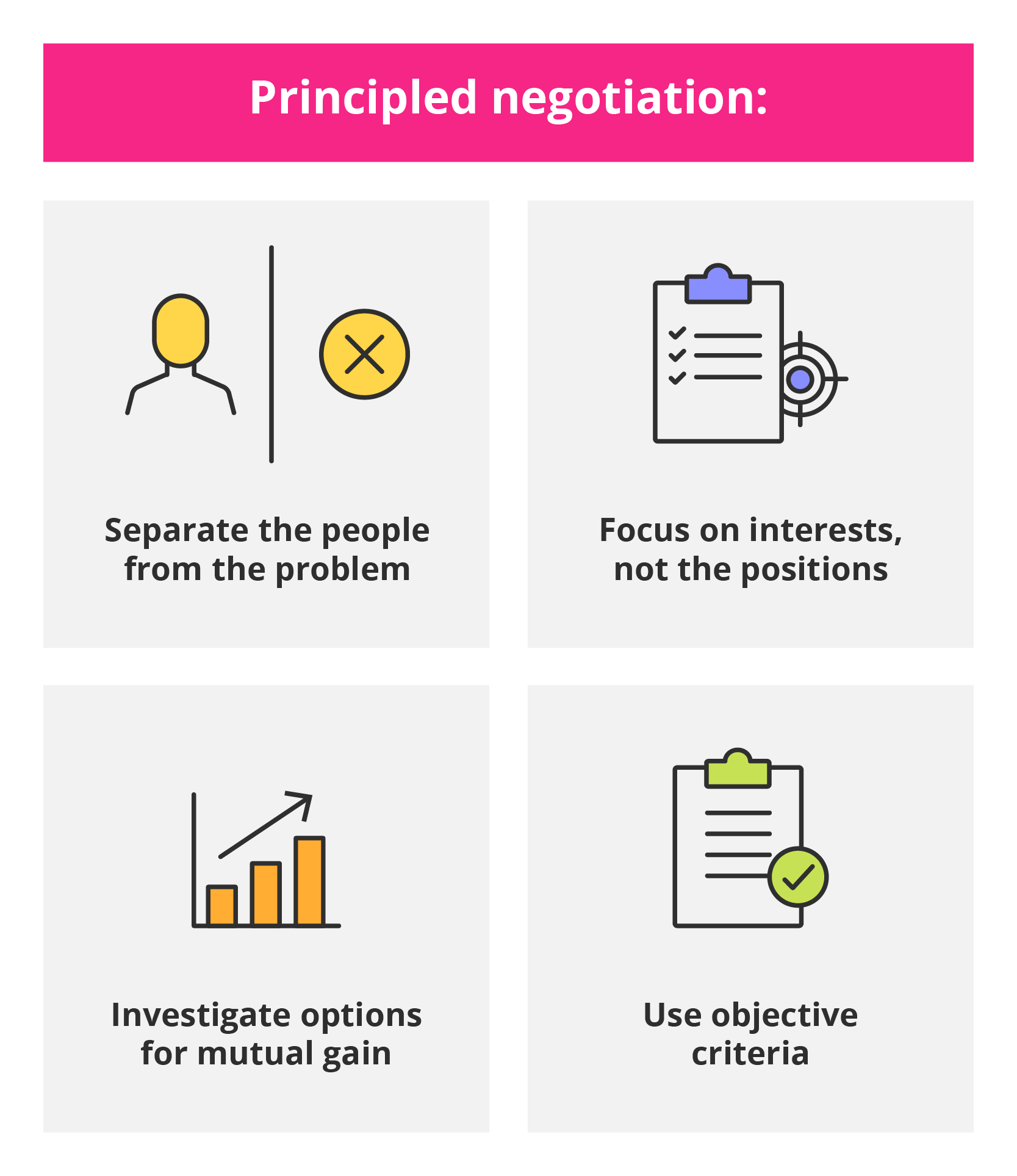

4. Principled negotiation

Attitude, strategy, and style are important elements of effective negotiation. People often assume that this can mean one of two things: either you negotiate in a tough and competitive way, or you take a friendly and accommodating approach. Principled negotiation introduces a new way of thinking about negotiation that doesn’t require you to be competitive or accommodating. By removing the issue from the people involved, principled negotiation takes a team-work approach to solving the problem.20

To help you achieve this, focus on these four elements of principled negotiation:

Separate the people from the problem

Choose to see the other party as a partner in your problem-solving by isolating the issue you’re both trying to resolve. Talk about the problem at hand, not about the person you’re negotiating with or how they’re related to the issue. Actively listen to understand their position and interests in the negotiation, and acknowledge these as part of the problem you’re wanting to solve together.21

Focus on interests, not positions

Recognise why the other party is negotiating, and the reason they have taken their current position. Their position defines what they want, and their interests define why they want it. If you focus on positions, you may end up making a compromise at best. However, if you understand the thinking behind the position, you may be able to come up with a solution that suits both parties.22 For example, if you’re negotiating with a roommate over who can have the last lemon in the fruit bowl, your positions are clear, being that both of you want the lemon. At this point you might compromise and cut it in half. You juice your half and throw the skin away, while your roommate grates the rind of the lemon to make lemon-icing, throwing the inside away. If you had asked questions and discovered why you wanted the lemon, you both could have walked away with more of what you wanted, creating more value for each of you and a win-win situation in the process.23

Investigate options for mutual gain

This is a brainstorming session that happens in the negotiation, where both parties try together to come up with as many solutions to the problem as possible. The aim is to problem-solve collaboratively so that the potential solutions belong to both parties and there is a shared sense of ownership when the final decision is made.

Use objective criteria

As the concepts of fairness and truth can be largely subjective, finding a standard that both parties rely on as fact can be critical in deciding what you both consider is a fair or unfair outcome. Whether this is the law, company policies, or the market price of an item, having a neutral standard to discuss issues against is helpful in pressurised negotiations.24

5. Cultural awareness

An informed cultural awareness should underlie any negotiation technique, strategy, or style. While it’s important to understand that a person cannot fit into any specific cultural box, there are particular social behaviours and experiences that will inform how they behave in a negotiation. Having a solid understanding of the norms and values of their culture before you enter into a negotiation is not only respectful, but will prevent miscommunications and misinterpreting behaviours as the negotiation unfolds.25 Most importantly, having the emotional intelligence to adapt your behaviour if your counterpart does not fit your cultural expectation is critical. For example, if you’re negotiating with someone from a predominantly formal culture you should prepare to behave in accordance with that. However, if you find that your counterpart is actually casual and you adapt to mirror this behaviour, it will be beneficial for you and the overall negotiation experience.

Negotiation cannot be scripted

Informed by these five negotiation principles, you should approach an upcoming negotiation slightly differently. However, regardless of how skilled you are in negotiations, it seldom unfolds perfectly. In his book The Art of Negotiation: How to Improvise Agreement in a Chaotic World, Michael Wheeler says, “negotiation cannot be scripted”.26 Your goals can change, unexpected opportunities may arise, or your counterparty may approach the negotiation differently to how you had anticipated.27 Agility and flexibility are just as important as thorough preparation and an understanding of strategies when trying to come to an agreement.

Develop your negotiation skills and achieve your desired outcome.

- 1 Noble, C. (Sep, 2018). ‘Conflict assumptions’. Retrieved from Mediate.

- 2 Shonk, K. (Feb, 2019). ‘What is negotiation?’ Retrieved from Harvard Law School Program on Negotiation Daily Blog.

- 3 Wins, M. (Dec, 2017). ‘7 key skills for successful negotiation’. Retrieved from Procurement Academy.

- 4 Shonk, K. (Mar, 2018). ‘Negotiation preparation strategies’. Retrieved from Harvard Law School Program on Negotiation Daily Blog.

- 5 Smiley, D. (Mar, 2019). ‘Negotiation frameworks, part 1: Ideal outcome’. Retrieved from LinkedIn.

- 6 (Nd). ‘Interests vs positions’. Retrieved from MIT Edu. Accessed 15 April 2019.

- 7 Smiley, D. (Mar, 2019). ‘Negotiation frameworks, part 1: Ideal outcome’. Retrieved from LinkedIn.

- 8 (Jul, 2018). ‘Reservation point in negotiation: Reach negotiated agreements by asking the right questions’. Retrieved from Harvard Law School Program on Negotiation Daily Blog.

- 9 Fisher, R., et al. (1991). Getting to Yes. Retrieved from Penguin Random House. Accessed on 15 April 2019.

- 10 Wachtel, D. (Mar, 2019). ‘Top 5 negotiation skills tips’. Retrieved from Negotiation Experts.

- 11 Fisher, R., et al. (1991). Getting to Yes. Retrieved from Penguin Random House. Accessed on 15 April 2019.

- 12 Shonk, K. (Jan, 2019). ‘Top 10 negotiation skills you must learn to succeed’. Retrieved from Harvard Law School Program on Negotiation Daily Blog.

- 13 Wood, T. (Nd). ‘Do you talk about your other negotiation options, or BATNA’s?’ Retrieved from Watershed Associates. Accessed 15 April 2019.

- 14 (Mar, 2019). ‘Negotiation techniques: How to predict a negotiator’s decisions’. Retrieved from Harvard Law School Program on Negotiation Daily Blog.

- 15 Kenton, W. (May, 2018). ‘Zone of possible agreement’. Retrieved from Investopedia.

- 16 (Feb, 2019). ‘Expanding the pie: Integrative versus distributive bargaining negotiation strategies’. Retrieved from Harvard Law School Program on Negotiation Daily Blog.

- 17 (Oct, 2018). ‘Creating value in integrative negotiations: Myth of the fixed-pie of resources’. Retrieved from Harvard Law School Program on Negotiation Daily Blog.

- 18 (Feb, 2019). ‘Use integrative negotiation strategies to create value at the bargaining table’. Retrieved from Harvard Law School Programme on Negotiation Daily Blog.

- 19 Shonk, K. (Jan, 2019). ‘Top 10 negotiation skills you must learn to succeed’. Retrieved from Harvard Law School Program on Negotiation Daily Blog.

- 20 Shonk, K. (Jan, 2019). ‘Top 10 negotiation skills you must learn to succeed’. Retrieved from Harvard Law School Program on Negotiation Daily Blog.

- 21 Doran, C.,et al. (Mar, 2017). ‘Separating the people from the problem in a negotiation’. Retrieved from MWI.

- 22 Webster, V., & Webster, M. (Apr, 2019). ‘Principled negotiation’. Retrieved from Leadership Thoughts.

- 23 (Nd). ‘Interests vs. positions’. Retrieved from MIT Edu.

- 24 Puscasu, A. (Jan, 2019). ‘Negotiation framework: Mutual gain and objective criteria’. Retrieved from Apepm.

- 25 Shonk, K. (Mar, 2019). ‘Cross-cultural communication in business negotiations’. Retrieved from Harvard Law School Program on Negotiation Daily Blog.

- 26 (Feb, 2019). ‘Negotiation research: Negotiation skills from the world of improv for conflict management’ Retrieved from Harvard Law School Program on Negotiation Daily Blog.

- 27 (Feb, 2019). ‘Negotiation research: Negotiation skills from the world of improv for conflict management’ Retrieved from Harvard Law School Program on Negotiation Daily Blog.